Whisker “Stimulator”

Northwestern SENSE Lab, Summer 2024

Project Lead

Skills: CAD, 3D printing, machining, experimental design and testing, engineering for research support, leadership and organization

Detecting Contact

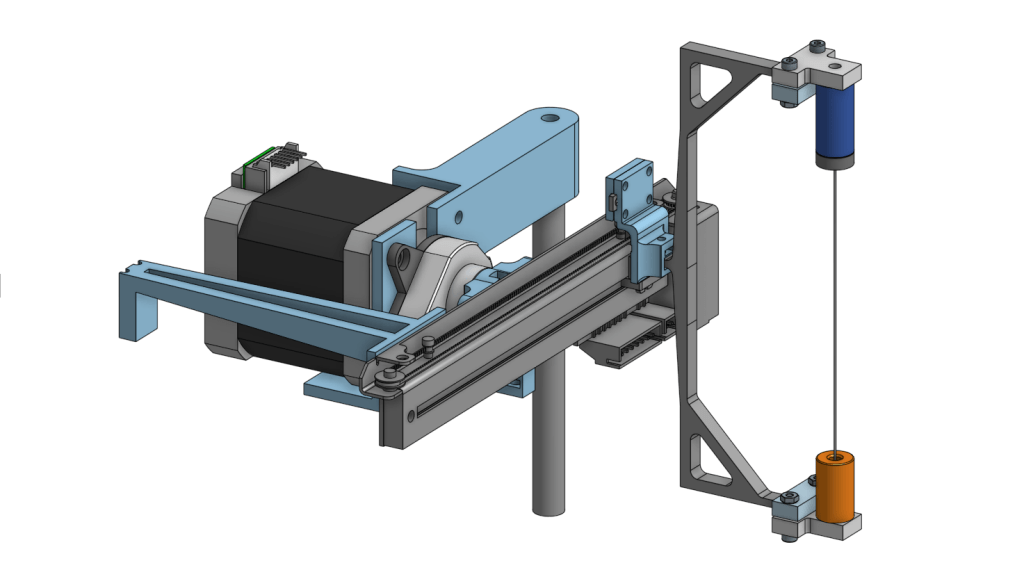

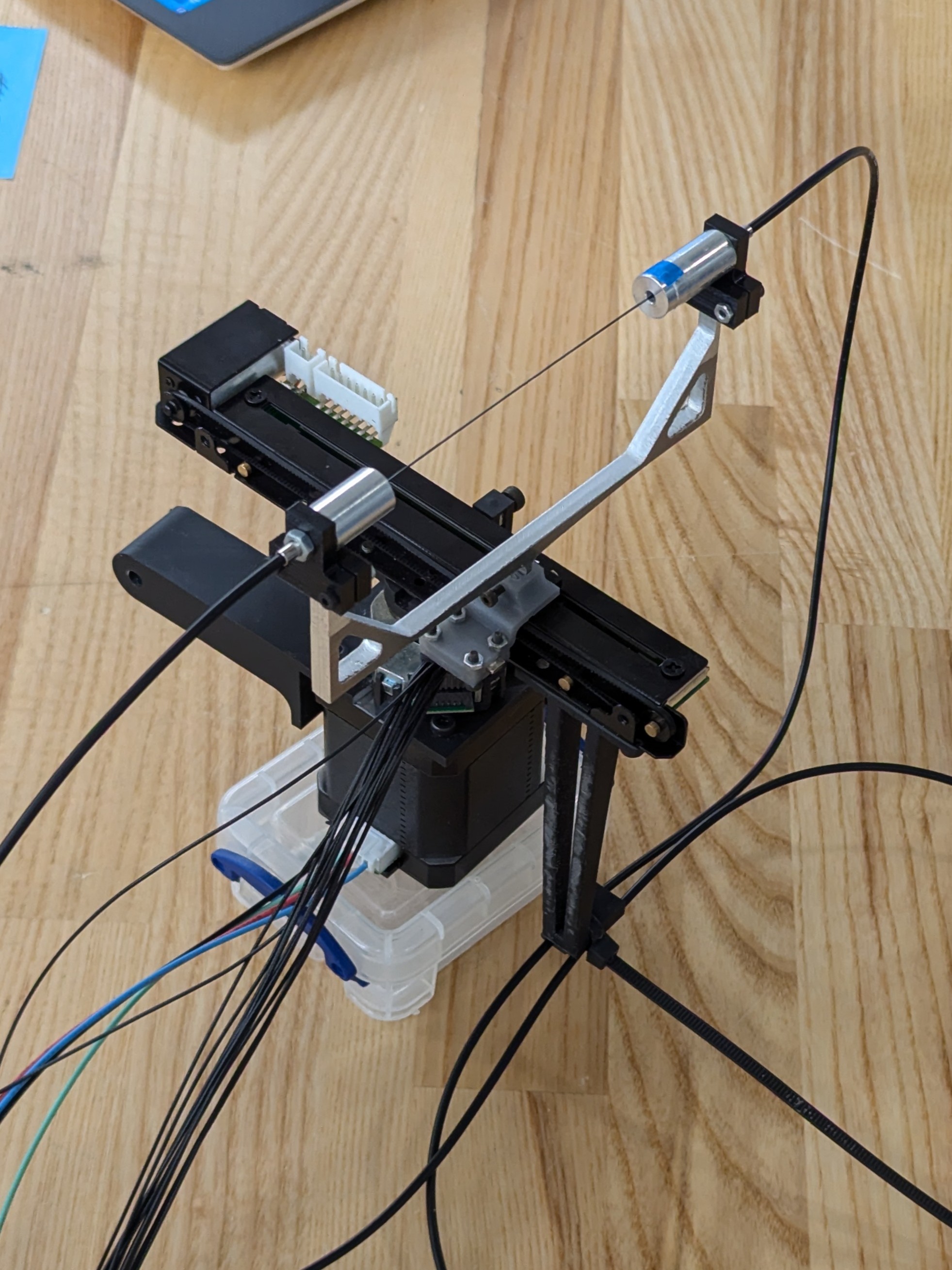

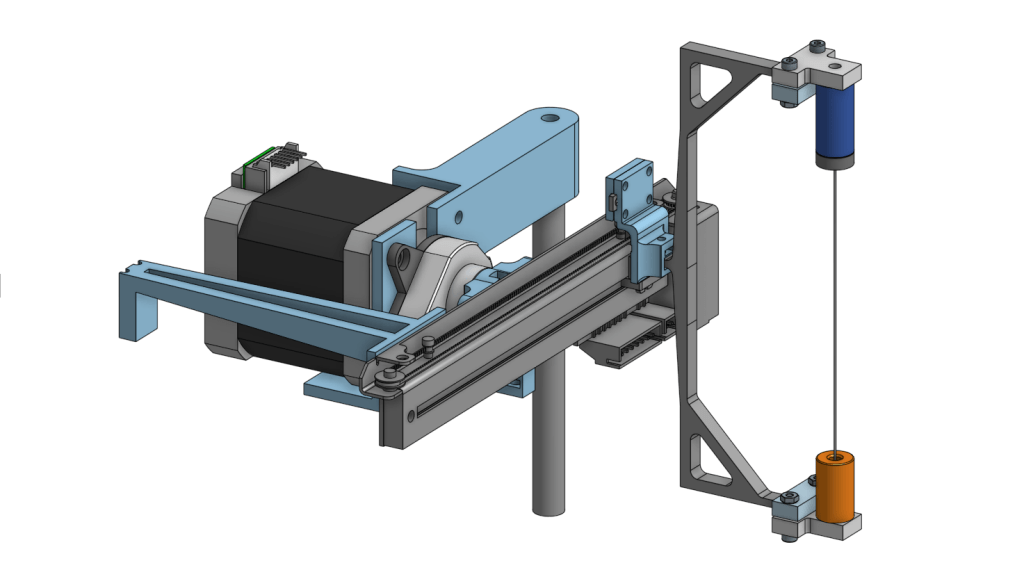

We were tasked with improving an existing whisker stimulating device being used for research in the SENSE lab. The lab is studying how rodents use whiskers to sense the world around them and needs a device to stimulate whiskers while also detecting contact.

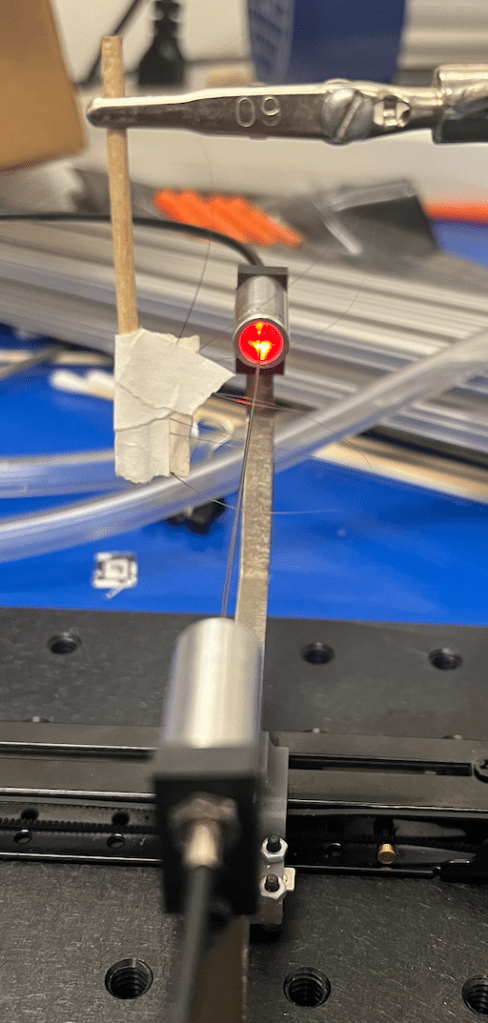

A thin wire sweeps across the whiskers, while a coaxial fiber optic beam is sensitive enough to detect them. The paper describing the original proof-of-concept device in detail is here.

The original device was degrading from use and plastic creep. The lab needed a more robust version of the device with better sensor characteristics.

My curiosity and interest in this problem resulted in me taking a leadership role in this project. I was absorbed in it; problems occupied my thoughts in my free time, and every day I was excited to make progress or try something new. It was so rewarding to see extensive iteration pay off in the final product.

Iteration, Failure, Iteration

Proximity and access to fabrication services and equipment enabled rapid and productive iteration.

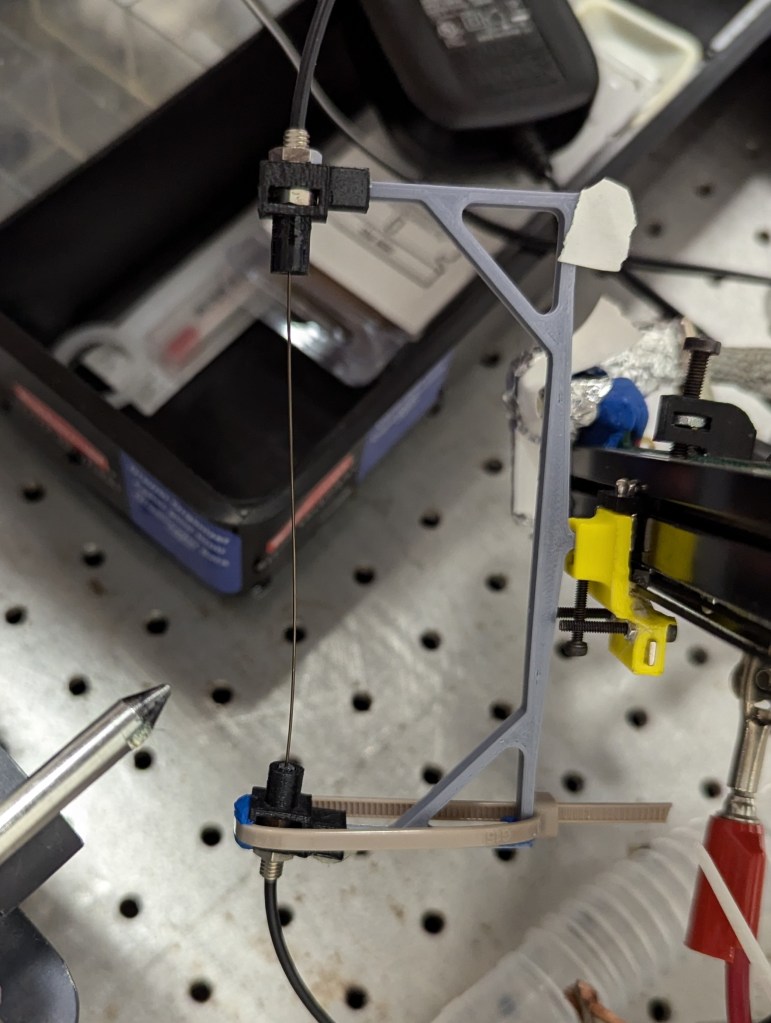

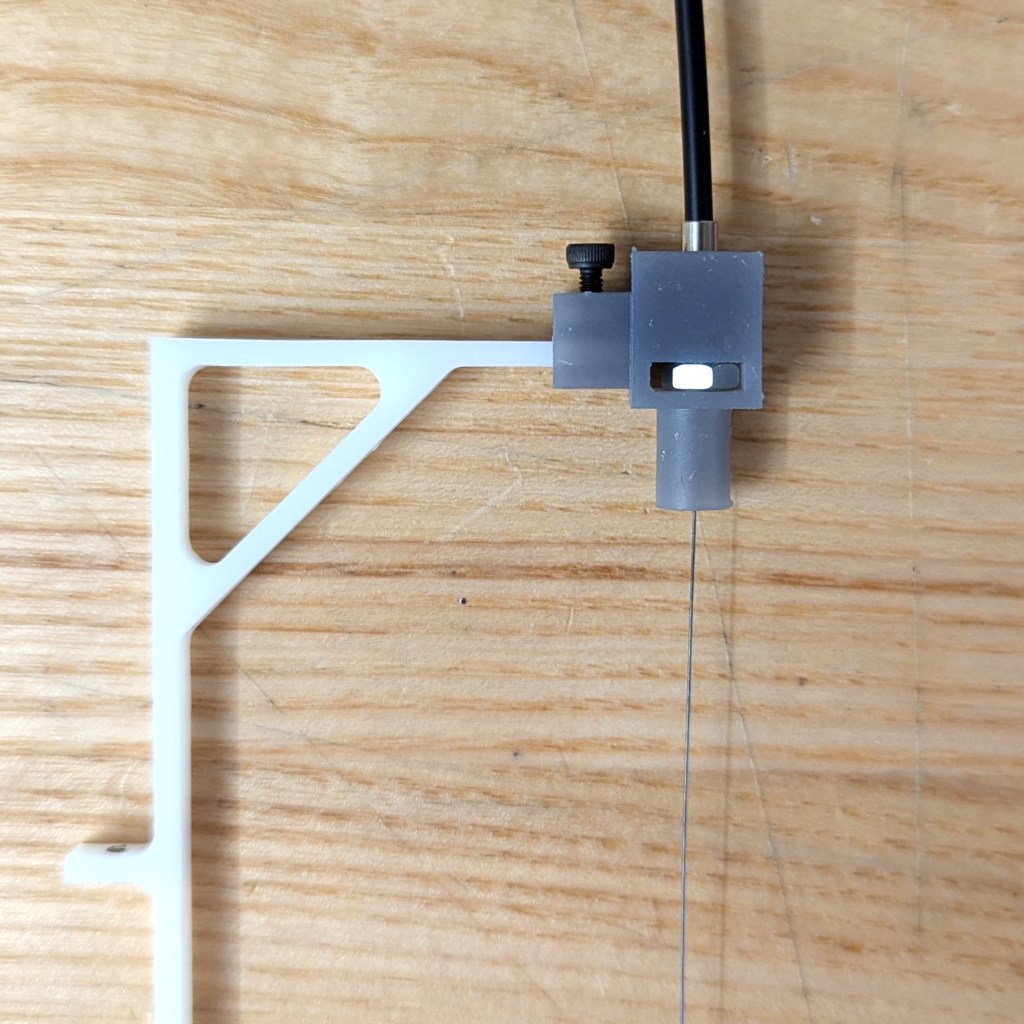

Our focus was on refining the carriage assembly, including the fiber optics and wire mounting. This was the area that was causing most of the problems with the original device.

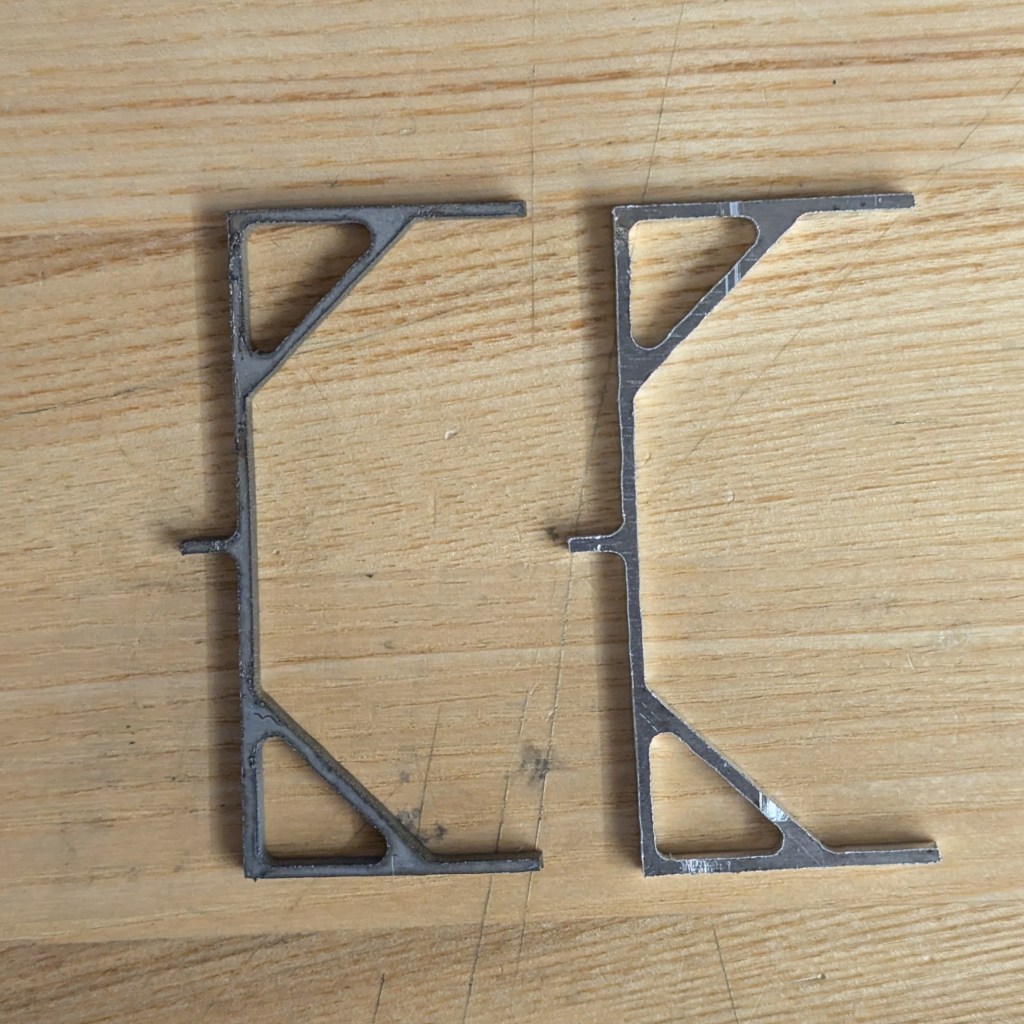

We started with testing several materials for the main carriage structure, seeking to improve stiffness over the original FDM printed PLA parts. Other printed polymers were quickly eliminated, as they provided little improvement.

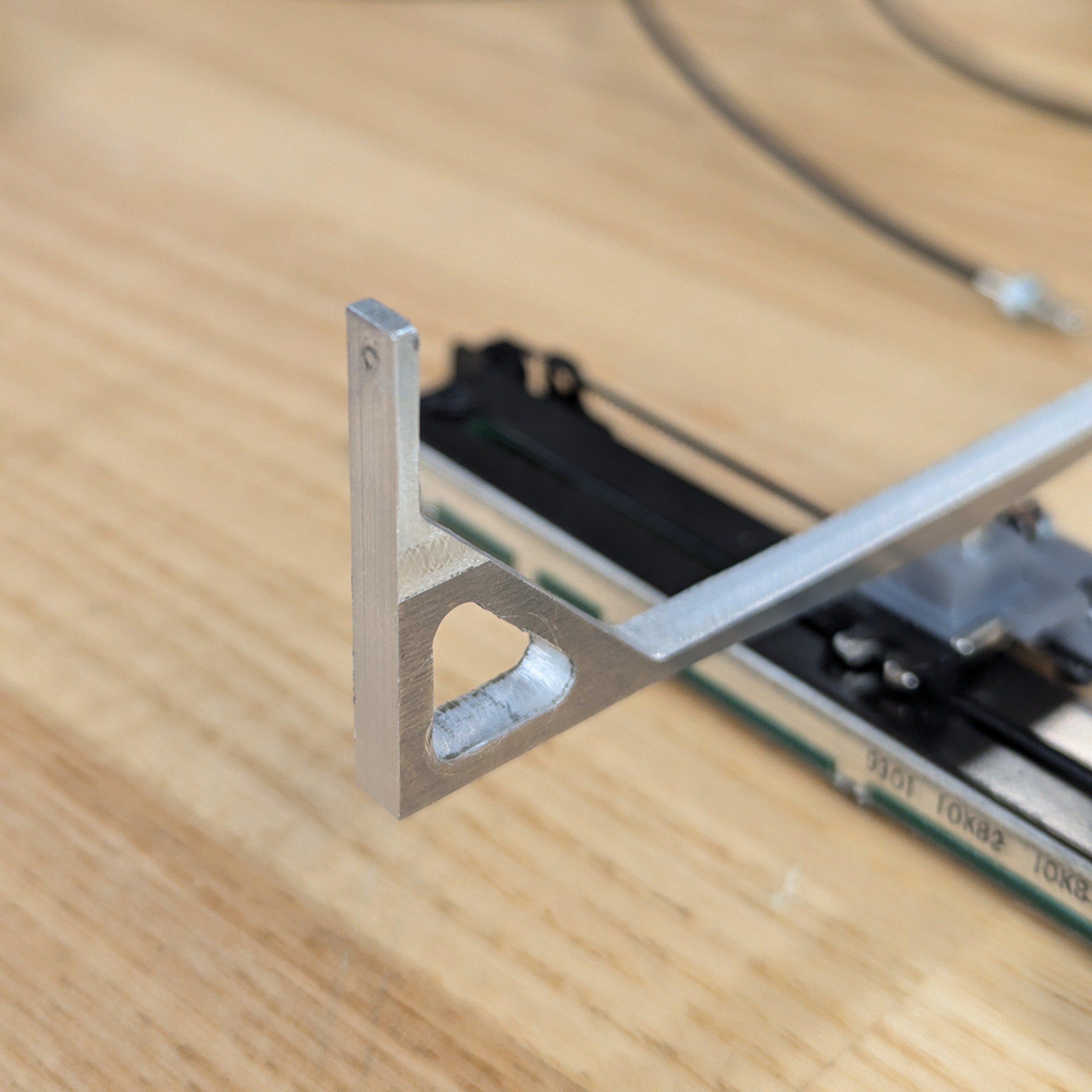

We then outsourced laser-cut titanium and aluminum versions, which were an improvement. Outsourcing proved to be cost-effective and allowed us to have several spare parts to work with and develop in parallel.

The laser cut parts were machined further on the mill to achieve better squareness and alignment.

The fiber optic and wire mounting was the most challenging part of this project. Getting the wire precisely centered and secured in the beam and then being able to align both ends was difficult.

We started by remaking the original design to get a better understanding of its limitations.

Our next approach was to cast the wire in epoxy in a nut. Centering the wire while the epoxy cured was imprecise, and we couldn’t get bubbles out of the epoxy.

This approach had worse clarity and sensitivity than the initial design, and we had no confidence in our alignment.

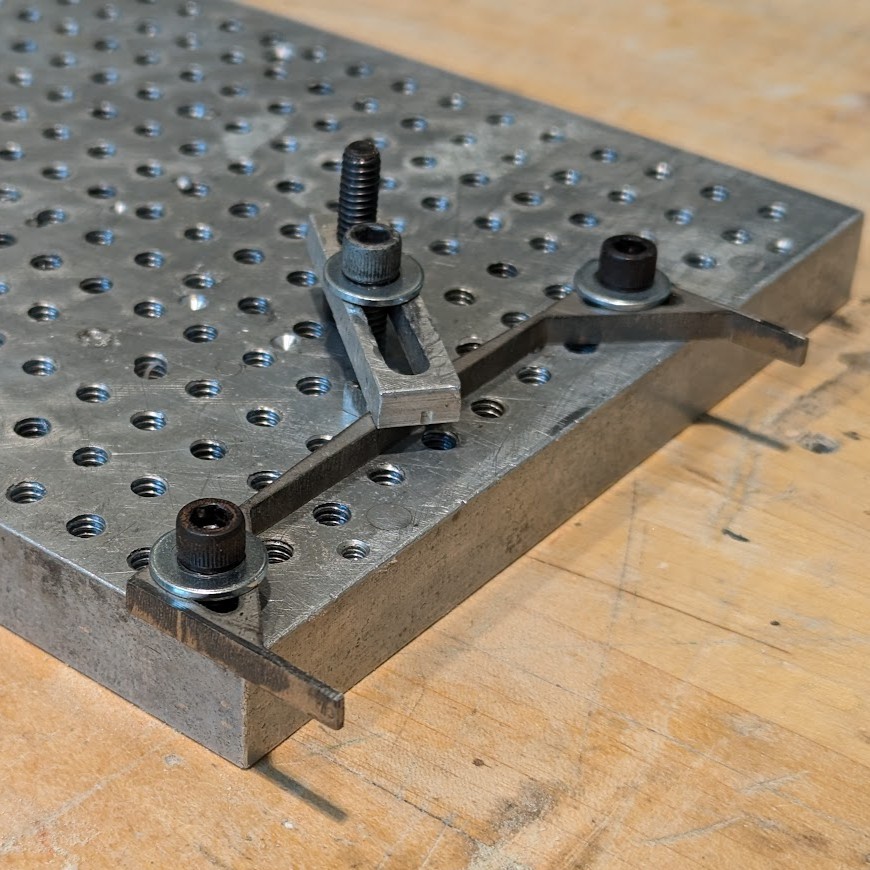

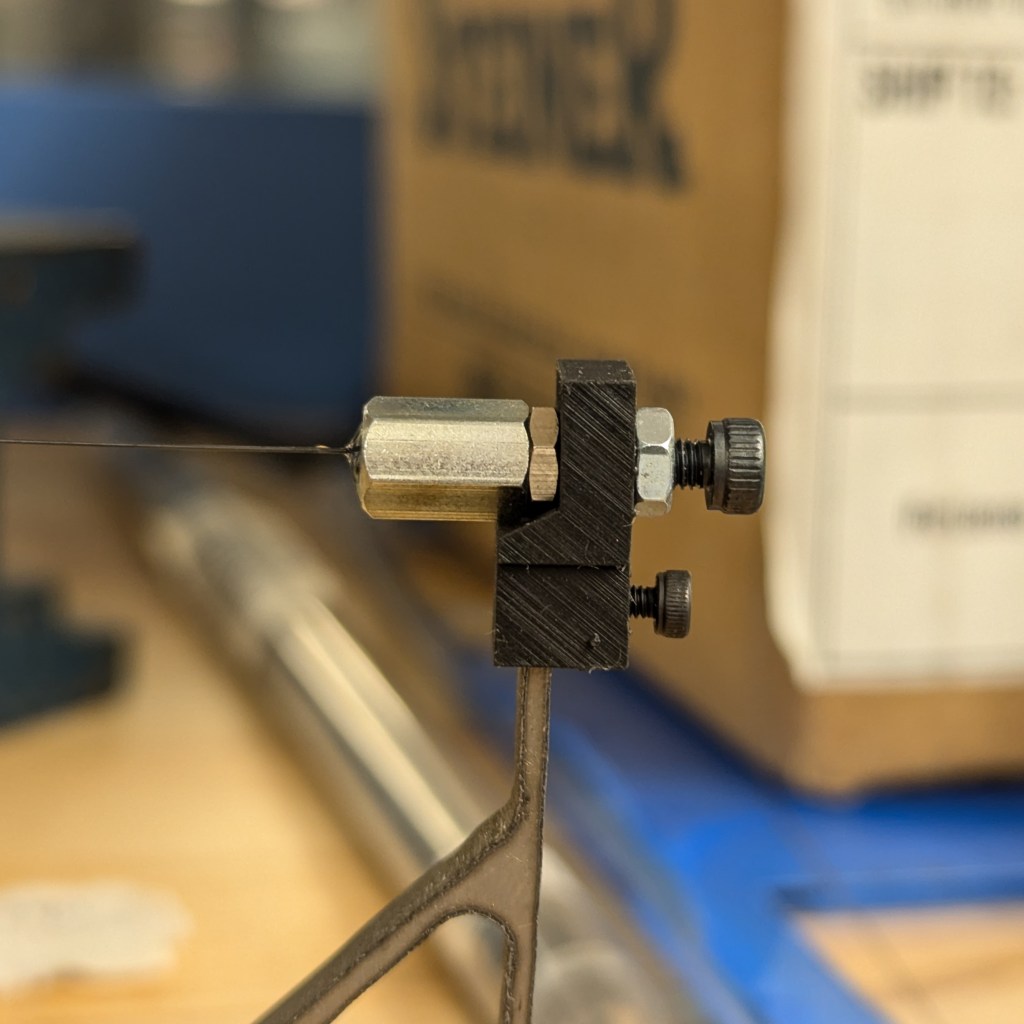

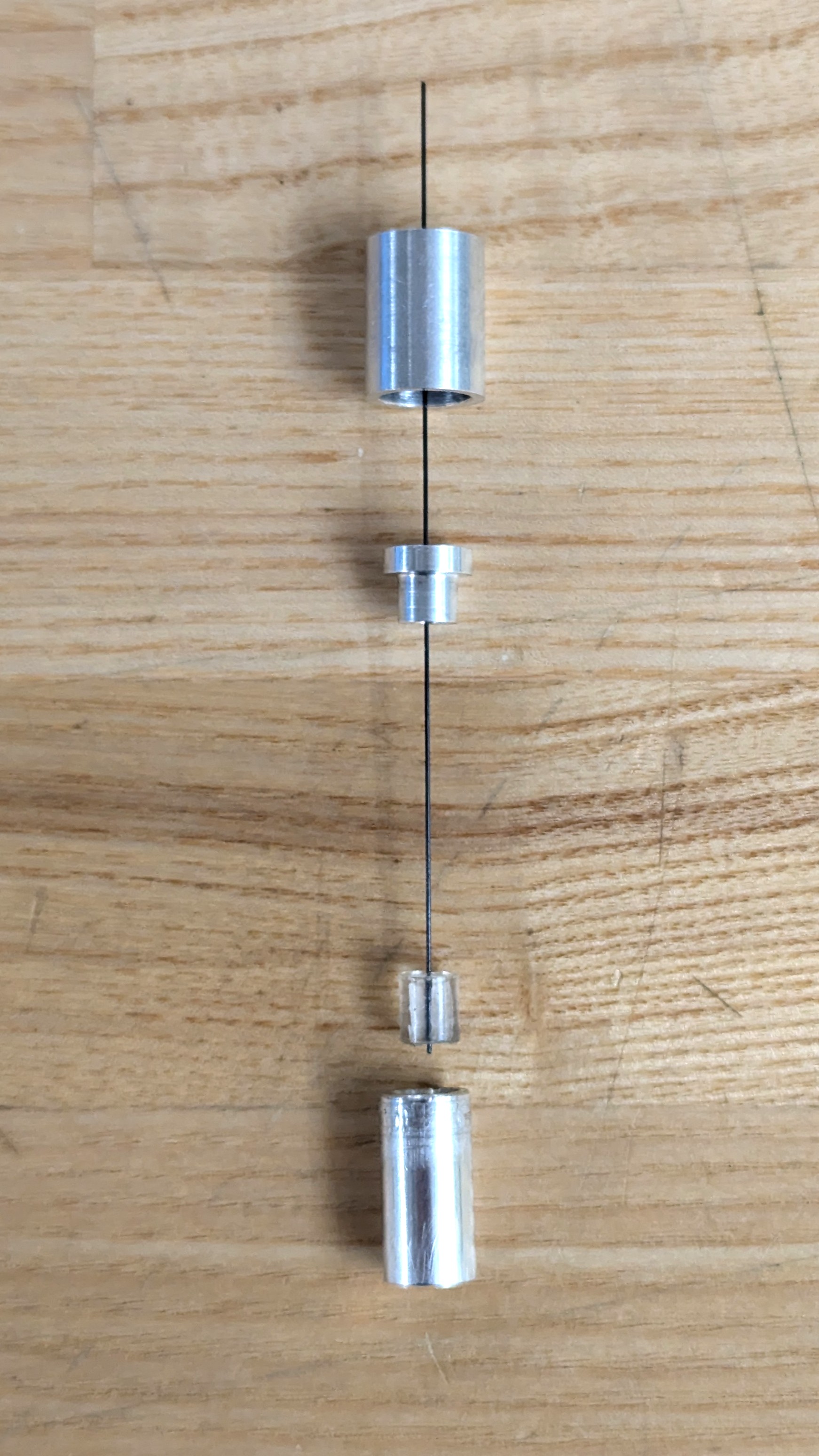

We then developed a set of machined aluminum couplers, using precision alignment jigs and a mix of machined acrylic and fishing tackle for holding the wire. This system was iterated on several times and ended up being our final approach.

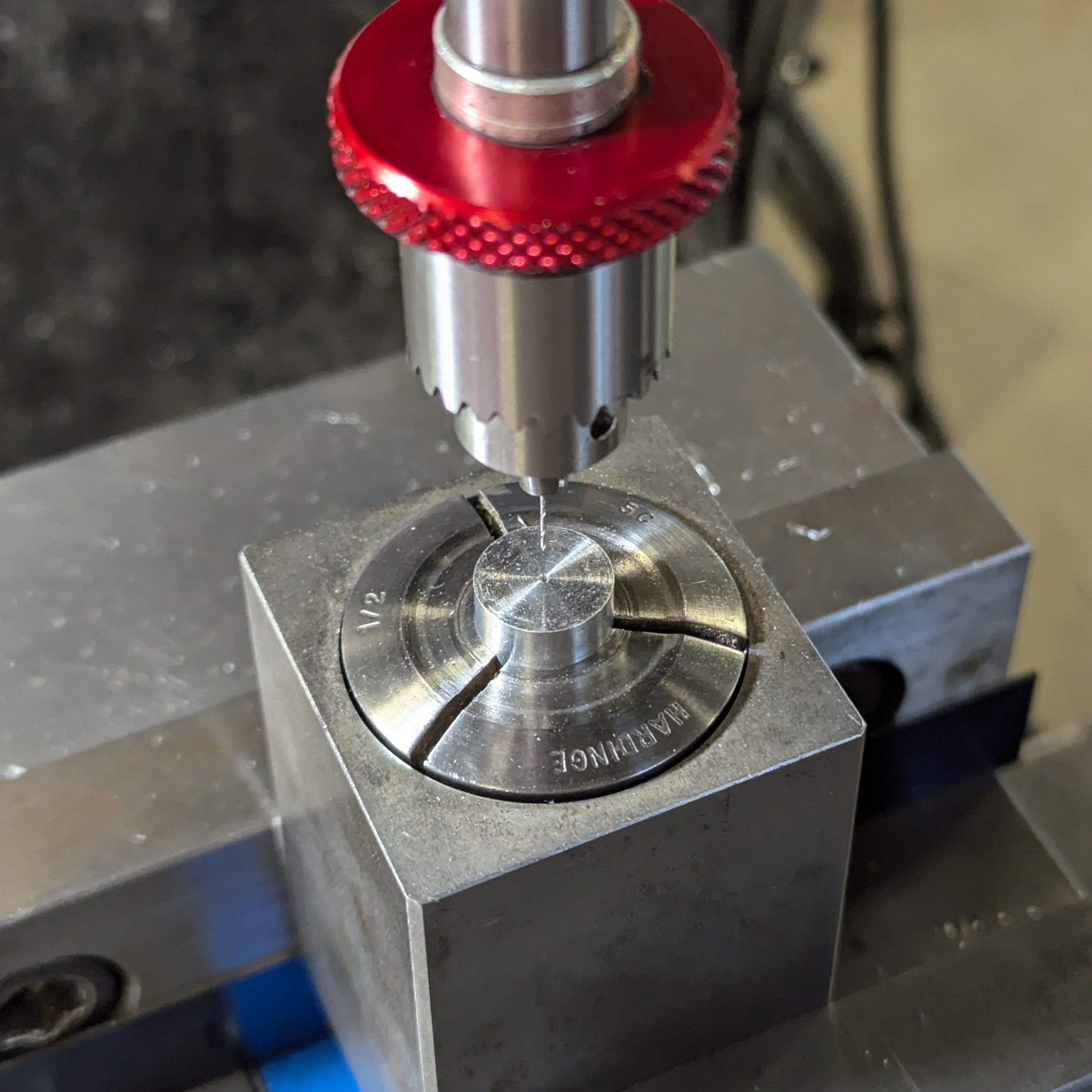

I did most of the design and machining work for this iteration, which included several precision sliding fits and some very small (and nerve-wracking!) drilling.

We received input on our iterations from our weekly meetings with the lab, as well as from bi-weekly design reviews with the rest of the intern cohort and our advisors. These meetings would help initiate new areas of interest, identify potential concerns or areas of development from the lab’s perspective, and give us a fresh perspective on the problems we were having.

We also tested every promising iteration with a micro-manipulator and a brush the lab had made with real whiskers, as seen to the left.

Our goal was to characterize the sensitivity and symmetry of the sensor. We did this by setting a threshold detection limit (a set voltage drop on the fiber optic sensor) and recording the distance from the wire where detection occurred with single-whisker contact.

Our final iteration had good sensitivity and symmetry. The lab had not done this type of characterization for the original device, and they were happy with our end results.

A Complete Refresh

In 10 weeks we were able to deliver an overhauled device that will be more durable and more precise than its predecessor. The lab is satisfied with our final product, the work we did to characterize the sensor’s behavior, and the documentation we provided when handing back the project. The device will be used in ongoing biomedical and robotics research.

I have a deeper appreaciation for learning through failure and thoughtful iteration after working on this project. Having prototyping resources and skills proved to be essential, in addition to robust testing and the incorporation of outside perspectives through our design reviews.

This is also one of the first projects I have had true ownership over, and that helped me progress as a leader. The value of taking intiative was reinforced for me, and I feel I started to learn how to utilize the skills of my team members (along with my own) to get the best result possible. I’m immensely proud of what we accomplished.

People

I’d like to thank Professor Mitra Hartmann and Kevin Kleczka of the SENSE lab, Professors David Gatchell and Michael Beltran, and the Ford prototyping shop professionals for their guidance and support.

The team consisted of myself, Benjy Braunstein, and Emma Luzio. I’d also like to thank them for their creative thinking and numerous cruical contributions.